LOVE STEPPED OUT—The Lemon Twigs pay tribute to their dad

Brian: Our dad was great when we were kids. He taught us the basics of every instrument and was always there when we had questions. Because we were five when we started, he made sure that there was instant gratification for us, as opposed to it being this really difficult thing. I remember initially he showed us how to play a beat without using the bass drum so we could get used to keeping time quicker, and showed me a one finger chorded version of Love Me Do, which got me used to playing while I sang. He and my mother had us doing harmonies when we were really young which really trained our ears and made it easier to hear chord changes as our proficiency at melodic instruments developed. Another thing they did was just talk about music all the time, and what they liked about a particular song. My dad would always point out things that the Beatles did that were clever as we listened to them. I remember there were a lot of times when he would use the dial in the car to pan to one side so that we could hear just the vocals of a song. I remember thinking to myself "how does he have all the tracks up there?"

Michael: I still listen to his records. I listen to them the way I listen to other music I love, and I don’t really think about how this guy is my dad. Every once in awhile I'll be listening and that thought enters my head and I get emotional and need to let him know as soon as possible how great his music really is.

Brian: What has rubbed off on The Lemon Twigs?

A love of harmony, interesting arrangements and chord changes, plus the joys of pop music! His music also serves as a reminder to us that working within a classic pop structure can be done very skillfully. It's definitely something that will impact our music going forward!

Michael: Well at first his clever and concise songwriting style influenced me to go against typical structure in an effort to rebel, but now I see that trying to create something unique within the confines of a fairly straightforward pop song is one of the coolest ways of writing songs, and often produces some of the best songs. I'd say that lately my Dad's music has been one of my primary influences in songwriting.

Brian: I think we were always aware that he had made a lot of records, because he was always recording at home when we were growing up. Probably the first one we were really familiar with was his children's album "Try Out A Song," because it was specifically geared towards kids, and I remember being really fond of it. That was done in 2001, so I would have been 4. Michael and I were actually on the cover of that one!

Michael: I always knew Dad’s records existed, and I'd heard most of the songs throughout my lifetime; the same way I was aware of The Beatles and Beach Boys because it was on so much in the house.

He was the best teacher. He showed us the basics on drums, bass, guitar, and piano, then let us find our own way. If ever we had questions about how to play something we were encouraged to ask. Both of our parents had great taste and did a good job of exposing us to music with great melodies and lyrics.

Brian: We still play his records. In fact, we play them a lot more now than we ever did when we were really young. I think that he's one of the most consistent and talented writers out there.

AN AUDIENCE WITH PAPA TWIG:

Obviously you adored The Beatles as a teen in the ’60s and The Brit Invasion, plus The Beach Boys, but were you into local area bands too?

Like a lot of kids my age, I saw the Beatles on Ed Sullivan, Feb. 9th 1964. It gave me an amazing feeling and my mom bought me a guitar that summer. The first lick I remember playing was from “The Man From U.N.C.L.E.”. Then “Satisfaction” and “Day Tripper” which I played wrong by one note. My memory before The Beatles is hazy, as if my life didn’t start until they came on the scene. I can remember where I was by each album.

Every night I would go to bed tapping out drumbeats on my pillow with two fingers. I was obsessed with The British Invasion. The DC5, Kinks, all of them. Of course I grew my hair as long as my schools would let me.

As far as The Beach Boys go, I didn’t get into them until 1971 with the Surf’s Up album. I heard the title song on WPLJ in NY, and I waited ‘til the end to hear who it was. I was fascinated by the chromatic melody (“beyond belief a broken man too tough to cry”) When the DJ said “The Beach Boys,” I became very interested. The following week I heard, “I Get Around” and was blown away, because I heard it in a whole new light, even though I knew it as a kid. They got me through the Seventies after The Beatles broke up, because their albums were out of print then, and I would have to search stores in the cut out bins to find them all, which I did. It was like when my boys heard them. I had eight years of BB albums all at once to listen to—their best stuff.

Re: Local bands: I would say The Four Seasons and The Rascals, and Burt Bacharach. I liked Motown and Stax, and a little later--Blues, like The Butterfield Blues Band, Mike Bloomfield, and BB King. That helped me with my guitar chops.

My mom took me to a concert at The Paramount in September 1964 hosted by the WMCA Good Guys, starring The Four Seasons, The Animals, Leslie Gore, Sam Cooke, The American Beetles, The Royale Guardsmen, and The Devotions. Music was my total world.

I always watched Shindig, Hullabaloo, and Where the Action Is. You had to seek out Rock music back then because the generations hadn’t turned over yet. The older folks were still in charge. The first time I heard “I Feel Fine” was on The Sandy Becker (children’s) Show. Puppets were singing it.

I used to stand outside of The Metropole Café on Broadway and 48th street and watch Gene Krupa and a local cover band. I watched from outside because it was a “Gentleman’s Club.” They would leave the door open just enough so you could just about see the topless “Go Go Girls.” Then I would go to the 48th street music stores and stare at the guitars in the window. I lived right there in the theater district.

How did you get into music?

After seeing The Beatles on Ed Sullivan, I started playing guitar, which I got at Sam Goody’s--nylon string, made in Holland. I was ten. The earliest music, I can remember hearing, was Gilbert and Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore. Somehow I heard it in first grade and it gave me that feeling. “When I Was Lad” was my favorite. The radio--pre Beatles, I liked The Four Seasons, Runaway, Let’s Twist Again, Sugar Shack, Michael Row the Boat Ashore, Don’t Let the Rain Come Down. Since I lived in the theater district, my mom took me to lots of Broadway shows. I saw “Oliver” with Davy Jones before he was in The Monkees. I loved, “Where Is Love?”

I have very old reel to reel tapes that my mother recorded of me singing in the bathtub when I was 2 and 3. She had an old Revere tape recorder, which I played around with when I was little. So music was always around. My mom loved Sinatra, as do I. She had a good voice and a good ear for harmony. My Dad, who I never knew, was a professional sax player. He played the horn break on “Let’s Hang On.” I found out about him years later through my half sister. That’s a whole other story.

Any teen garage bands?

Not until the age of 20 was I in bands. My teenage years were spent in my room writing and recording songs on a Concord reel to reel tape deck. I think that deck is in “A Clockwork Orange” when Alex is being tortured with Beethoven. Anyway, you would record a guitar on the left channel, then you would bounce that to the right channel along with a live overdub like bass. Now you had that guitar and bass, both, on the right channel and you’d bounce that back to the left along with another live overdub like drums. Every time you did that, you would lose a generation, so by the time you got to your eighth OD, you’d barely be able to hear your original track. You could get very bizarre sounds. I didn’t have a drum set. I used a copper ashtray with jacks in it for a sizzling cymbal that I hit with a pencil eraser, and a piece of loose-leaf paper for the snare, and my mattress for the kick drum. I trained myself to play both the snare and kick with my left hand so that I could ride the cymbal with my right. My kids grew up having all the instruments and recording gear that they needed.

What were you doing before the release of your solo albums?

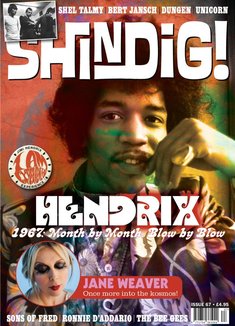

When I was twenty, I worked for free in a recording studio, which is where I met a lot of friends who I still have today. It was called Dimensional Sound on 54th street and Eighth Ave, run by a guy named Ed Chalpin. He was Jimi Hendix’s manager before Jimi made it. He signed him for life and got very rich. There’s an album somewhere of me playing bass with Jimi Hendrix. It’s Curtis Knight on vocals and Jimi on not so great rhythm guitar mixed low. Ed hired a guy to play like Hendrix and sold it as a JH album. All I remember about it is playing the Dizzy Miss Lizzy bass lick over and over. I got $15 per track.

I learned a lot there about analog recording. I recorded the “I Was Your Window” demo there.

This studio also recorded “Sound Alike” records. “Get 25 Hits for $10. (not the original artists).”

We would have a meeting trying to predict what was going to be a hit so we could get it out in time. When I say we, I mean he. We boiled it down to eight singles, which we put on cassette and took home for the weekend to learn. I played the bass part. We would come in Monday and record eight tracks with the original record playing in our cans (headphones). I’d hear myself singing “Laughter In the Rain” on the TV commercials. Most songs would have an eight bar verse, but once in a while you’d get a nine bar verse and the drummer would do a fill not realizing, so he had to do an extra fill into the chorus. They were awful. “Woman Tonight” by “America” was a nightmare because no one could figure out where the “one” was. I still have a recording of myself doing all the harmony parts on “Who Loves You” which was similar to “Don’t Worry Baby.” I sang “Nights On Broadway” which sounded like a Rich Little impression of The Bee Gees--$15 per track and $7.50 per overdub.

I was also in a cover band that did Sixties and Seventies music. We actually started rehearsing my song, “Take In a Show” but then it fell apart because we rehearsed more than we ever played gigs.

When you cut your debut in 1976 your love of the ’60s is so evident. You play everything yourself, right? Was Emitt Rhodes an inspiration?

Sure. I was aware of ER and of course Paul McCartney, playing everything themselves, but it was just as much out of necessity. At that point I liked the parts I came up with for my own songs. I would hear the parts as I was writing the songs and it was awkward telling people what to play. Also I couldn’t get a band that would just do my stuff. Musicians wrote their own songs and wanted to do their songs too.

Did acts like The Raspberries feel like a close fit?

I liked The Raspberries. “Tonight” and “Overnight Sensation” are great. That scream that Eric Carmen does on “I Reach For the Light” really gets me. The fact that they dig The Beach Boys as well as The Beatles makes them a close fit. I always leaned more towards Badfinger and the “Emitt Rhodes” album, but yeah, I liked them. Still do. I don’t look at any of that stuff as nostalgia because I never stopped listening to it.

Where and how did you record this?

I was living at home in Manhattan on 54th street between 7th and Broadway diagonally across from the Ed Sullivan Theater, so I recorded it in my room. I had been writing since I was eleven and I felt that I finally got the hang of it. The first song that I thought was good was “It’s Spring Too Soon” influenced by Bossa Nova (Antonio Carlos Jobim), but sung like Carl Wilson. I went over my songs up to that point and took the best parts and wrote new songs with them. I thought I had some good music, but now I had a better idea of structure and lyrics and I didn’t want to waste them.

I recorded that album on a Teac 4 track, ¼” reel to reel, that ran at 7 ½ and 3 ¾ ips. You can hear, on “Nice Meeting You Again” and “Love Stepped Out,” the speeded up guitar that sounds like a thin piano. I recorded the guitar at the slow speed and when I played it back at the fast speed, it was an octave higher. I filled up 4 tracks with drums, bass, rhythm guitar, and lead guitar. Then I mixed them in mono to my ¼” Tascam two track. Then I took that mixed tape and put it on the 4 track, using only the left channel, and that left 3 tracks open for vocals. I never threw out the instrument mixes, so when digital came along, I was able sync up the vocals with the original tracks, therefore saving 2 generations. A lot of work. Digital is a lot easier, but my sons love analog so that’s what they use. They have much better analog equipment than I had. They have a big 24 track with 2” inch tape.

Was it a private press? Or was Homburg a small local label

My albums were never pressed or released. Homburg Records is my own label named after the Procol Harum song. I had a group called, “The Noise” and we recorded a single called, “Smokin’ In Bed”, which I wrote. (My version is on the “Falling For Love” album.) That one, we did press 300 copies. We sent it to Billboard and they made it one of their Top Ten Hit Picks, but we didn’t have enough 45’s to back it up.

We didn’t have all the social media back then. I didn’t release my stuff until the Internet happened, where there were outlets like CdBaby.

Did the album receive any local airplay?

No. I didn’t have anyone to help me, and I was no good at networking.

I always thought if I could get it to some artist I respected, I could get somewhere. But I never could. The Lemon Twigs did that with Foxygen through Twitter, and Rado recognized their talent. He got the ball rolling. He deserves a lot of credit! Rado and his band heard my stuff and became big fans and that really inspired me. My kids love the “Take In a Show” album, which made me take another look at it.

I did have a manager (Lanny Lambert) in 1981. He really liked the “Falling For Love” album. He took it around to A&R guys’ offices, but no one took a chance. I took “Take In a Show” to a guy named Rick Stevens at Polydor. He gave me an appointment to play it in his office. He threaded up his reel to reel, listened to a bit of each song and fast forwarded. Half way through the tape, he stopped and said to me, “Not only do I not hear anything worthwhile, but I don’t even hear potential.” I’ll never forget that—kind of sadistic me thinks.

I sent the song, “Falling For Love” to Art Garfunkel, who actually received it and wrote me back saying, “I gave it the fair listen, so thanks but no thanks.” I still have the letter--from Staten Island. Thanks for the autograph, Arty!

Did you play out?

I played out with The Noise, The Press, and The Firemen. We did our originals in places like Folk City, CBGB’s, Kenny’s Castaway, and others. Then we became a cover band called, The Rock Club, where we played Sixties and Seventies music. We needed to make some money. We also played many Irish clubs that wanted rock and roll. I played with Tommy Makem for twenty years, so I knew the Irish scene. They were much nicer than the American clubs. They gave you dinner and drinks. If you didn’t have a lot of people one night, they would apologize to you. The pay was pretty decent. The American clubs would say, “We don’t have enough money in the register to pay you.” So much for the “guarantee.”

How did you land ‘Falling For Love’ to be covered by The Carpenters?

That’s an example where the song got to the artist. The Carpenters had their own office at A&M in California, run by Richard Carpenter’s cousin. I sent it to that label, and to their agent, and to their manger—three places. Richard himself listened to it and wanted to record it. He also complimented my version. He sent me a 50/50 song publishing contract. Their company was called “Hammer and Nails Publishing.” They recorded it with Karen doing a rough vocal. She died before doing a final take. Richard said her vocal wasn’t good enough to release, so that was the end of that. I never even heard their recording. I’ve seen the title on Carpenters web sites under “Lost Treasures.”

What did you do between 1976 and ‘81? Why the long break? Essentially the album maintains the feel of the debut, if maybe a little more refined.

I was writing and recording songs for the second album (Falling For Love). It was more refined because I got better equipment—more tracks. I bought a Teac 80-8, half inch tape with 8 tracks, at 15ips. I didn’t have drums or keyboards, so I had a plan. I would record all the other instruments to a click, along with my vocals, on the 8 track. Then I booked a studio for two weeks, transfered everything to their 16 track deck, added drums and keys, and finally, the mix. So that kept costs down. I had to book a motel too because the studio was in Connecticut. It came out pretty good but it was a backwards way of doing it. You should do drums first, then record the rest around that. It would have been a little tighter that way. That’s why “Emitt Rhodes” was tighter than “McCartney.” It’s obvious that Paul did a piano or rhythm guitar first and no click. When you do it like that, you can’t tell when you’re speeding up and slowing down, until you try to overdub to it. The way I recorded the first album was more the correct way. I did the drums first, but I didn’t have a lot of tracks.

What inspired to you stick with the classic pop framework?

It’s just the way I write. I had a friend who was always trying to follow trends to be successful. He even took a stab at disco. He would come to me for a catchy chorus. He was always able to write good verses and lyrics, but he said he couldn’t write great choruses. So I wrote some songs with him that went nowhere. They were good songs. I still have them. That’s when I decided that I would stop worrying and just write in a style that I like. Of course you’re always influenced a little by what’s going on at the time. Sometimes I’ll write a song in a different genre because of a title I’ve come up with. On my new album, “The Many Moods of Papa Twig,” I have a song called, “A Drunk Man Speaks a Sober Man’s Mind.” That sounded like it had to be country. A good friend of mine, Bob Mastro, played pedal steel on it. “Smokin’ In Bed,” to me, had to be a hard rock song. I’d love Paul Rodgers to sing that one. My vocal is a bit tame.

Another two years passed before Good For You was released… and again it continues the Beach Boys/Beatles feel. It doesn’t sound very 1983 at all. What were your aims for your solo records at this time?

Procol Harum is a big influence too, but since they’re not as big, you don’t notice. The sound of the albums has a lot to do with whatever gear I had at the time. My friend, Nick, gave me an old RMI electric piano, so there’s a lot of that on the album. That album may be the least produced of the three because I considered them to be demos for other artists to do. “Part Time Lovin’ Is a Full Time Job” was written for The Pointer Sisters. I’m singing it but it’s written for a female. “Love Up My Sleeve” was written for Gary US Bonds who had a big hit that Bruce Springsteen wrote for him. My girlfriend played flute so I have a flute on a song called, ”Amanda Lynne.” I didn’t have a mandolin, so I used a twelve string acoustic to simulate the mandolin part. “Suite 16” was my Chuck Berry tribute. Michael likes that a lot. I’m hoping that The Lemon Twigs will do a more rockin’ version of it. “Good For You” was written around an open D guitar tuning that an Irish musician taught me. “Next Time and Time Again” is very Bee Gees. “Thinking Out Loud” is probably the most Beatlesque song on the album. That album was recorded on my Teac 80-8.

Pop like this has always held its place in film and TV. This is something you have worked in too, right?

I did two jingles that ran during The Today Show, Donahue, and The Mary Tyler More Show. I even did one for The Muscular Dystrophy Love Run. And if you think that “The Muscular Dystrophy Association” is easy to make sing well…

I had my first taste of getting ripped off back then. This director wanted me to write a jingle for a Sealed Sweet Grapefruit commercial. He said he couldn’t come up with an idea for the spot, which was supposed to promote grapefruit as being healthy. Just so that I would get to do the jingle, I came up with the line, “Sealed Sweet Grapefruit—The Stay In Shape Fruit”. That was the theme in my jingle. Well I never did get the jingle, but one day I’m watching TV, and at the end of the spot, the narrator says, “Sealed Sweet Grapefruit—The Stay In Shape Fruit.” It was also written on the screen. He stole my line but never used my jingle.

This year, I got a great song placement on the TV show, “New Girl.” My kids were meeting with the music supervisor, Manish Ravel, who was interested in using some Lemon Twigs material. The kids said, “You should hear our Dad’s songs. They’re great!” They listened and told me that their office are now big fans of mine. They used “Take In a Show” during a bar scene, and paid me a crazy amount of money. I did that recording in 1976! I wish they would call for another song.

Which of the three albums is your favorite? And do you view a theme running through all three?

Brian’s favorite album is “Take In a Show”. Michael’s is “Good For You.”

Mine I think is “Falling For Love” probably because It’s the most produced album.

The only theme I can see is trying to write good songs with good words. If it’s a love song, I try to say it in a different way and with a certain angle or interesting title. I engineered and produced them all. Do you think there is a theme?

Please let me know if the recording process differed across the three albums and if any other musicians were involved.

The recording process, I referred to earlier.

Occasionally I use other musicians. “Take In a Show,” I did everything. “Falling For Love,” I used a drummer named Charlie Scibetta on half the album, and I played drums on the other half. Ed Fox plays piano,

Amanda Ettlinger plays the flute solo on “You Played Too Rough.”

Sam Burtis plays the trombone solo on “I’m On To Something.” On “Steps,” Jimmy Bralower plays drums, Bill Horowitz plays piano, with myself on bass. We recorded that track playing together at the same time.

“Just Passing Through” was the band I was in called,”The Noise.” We recorded that track all together as well, with Nick Lohri on guitar and b.g. vocal, Chris Scotti on bass and b.g. vocal, Buddy Zech on drums,

and myself on piano, guitar and lead vocal.

How do you view the albums now?

I’m appreciating them more and more since so many people seem to like them, including my boys. Social media has really helped with that, and The Lemon Twigs always giving me a mention, doesn’t hurt either.

Pedro Vizcaino called me and said he wanted to put it out on his label, “YouAreTheCosmos” Records. Darian Sahanaja told me through Facebook message that he loves my stuff as well as The Lemon Twigs. He’s the main man behind Brian Wilson and The Zombies Odessey and Oracle Tour. I’m meeting him soon at Town Hall for The Zombies’ concert. I have so much in common with him in regards to music. Last night we had a talk about Brazil ’66. That was a real thrill to get his approval. His band, “The Wondermints” is amazing!

Your sons have clearly drunk a little of your magic potion. It must be amazing to see them doing so well. What thread runs from your music into theirs? It’s definitely there.

We like a lot of the same music and because it’s in the genes, we will make similar musical moves, like going for the same harmony when we’re fooling around singing together. They did all the same things as kids that I did. The weird thing is, they’re doing it to the same music. When they were little, they would be in front of the TV watching The Beatles and pretending to play guitar. They’d say, “Look. I’m Paul.”

They’ll discover a new chord or chord change and get inspired to write a song around it. I did the same thing. They spend hours and hours recording, which I did when I was younger. I wish I had that kind of drive today. I’m glad that they’re getting successful and receiving accolades from people like Elton John, Gilbert O’Sullivan, Gary Brooker, The Zombies, Questlove, and more. Mary McCartney digs them.

They’re touring the world, selling out shows. It’s thrilling. Even when they were younger, they were successful actors on Broadway, TV, and movies, and they’re great kids--Very funny and smart. We’re similar in that we love melody, chord changes, and vocal harmony. I guess that’s the thread.

They play classical guitar, which I do not.

When they were learning to play, I would train their ears to hear chords. Not by naming the notes in a chord, but by playing them certain chords and progressions on piano and telling them what songs utilize them. I’d play them an augmented chord and say, “That’s the kind of chord The Beatles use at the beginning of “Oh Darlin’.” I pointed out all those George Harrison songs that use diminished chords. There are certainly a lot of those. The end of “She Loves You” is a sixth chord. Then I would test them. They have great ears. They were born with them, so it wasn’t very hard to pass on what I knew.

They’re excellent musicians and songwriters and singers.

I miss them a lot when they’re on tour. They miss us too, which is nice.

Esteban Cisneros interviews Ronnie D’Addario for La Pop Life April 8, 2017:

Ronnie D'Addario--Keep an eye on the name. It matters because it is a name that adds to the encyclopedia of pop. It took us forty years to recognize him as one of the great songwriters. It is not our fault, however: this is how the world works sometimes.

The tremendous thing about this story is that, in addition to its depth and how fascinating each episode is, it continues to be written and is far from final.

Allow me to better explain: Ronnie D'Addario composed and recorded some of the most impressive pop songs since the late 70's. They just never found their way to the radio or to the racks of the big record stores. One of them, even, was destined to be a hit for the Carpenters in 1981, but it did not happen.

He was a session musician, sound engineer and, for years, backed up Irish folk legend, Tommy Makem, of The Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem.

Ronnie’s songs deserved better luck and recognition. Now his music comes to us almost as a novelty, well into the 21st Century, thanks to the social media network and the craving of people dissatisfied with the current music scene.

Everything finds its place. Ronnie is the dad of Brian and Michael D'Addario, better known as The Lemon Twigs. The talent, of course, is inherited and how. The twist of fate is that the children (whose “Do Hollywood” 2016 album is a damn masterpiece) have forced us to listen to the father, and now we understand.

A new anthology of great successes has surfaced.--a “Best Of” LP and a box set of three compact discs containing the first three albums by Ronnie D'Addario, (released April 7th on the record label, “You Are The Cosmos”). It is a piece of pop history that must be had and studied, because the father/sons parallel worlds of this narrative are what will allow this music to live on and on.

We need new heroes, new legends, new songs. Checking the past is worth much, because there is much to discover-- A confirmation that there is still great music out there to be enjoyed and to make us feel alive.

We talked to Ronnie D’Addario about his career, his songs, his records ... and of course, the Lemon Twigs—quite an honor.

Could we start with a description of yourself? Who is Ronnie D’Addario?

I see myself first as a songwriter, then a musician and singer. To support those things, I engineer, arrange, and produce. That’s why I bcame a recording engineer in the first place--to get my songs on tape, and now digital.

I’m a Dad. My kids are the most important thing in my life. My wife, Susan and I really miss them when they’re on tour, and they miss us. Humor is important. My boys and I not only share similar musical tastes, but we like a lot of the same comedy. Brian and Michael are very funny too. We love Kevin Meaney, Monty Python, Johnny Carson, John Mulaney of the new guys.

How did your interest in music begin? How were your formative years?

The biggest spark was seeing The Beatles on Ed Sullivan in 1964. My mom bought me a guitar that summer, and I was off and running. I remember some music before The Beatles hit, like “Let’s Twist Again,” but the Fab Four was the big one. My formative years was a series of ten schools, mostly boarding schools, both Catholic and private. Back then there weren’t a lot of kids that played guitar that young, so I was always the kid that played guitar in each school. Even before I played, three other boys and myself would sing Beatle songs in the schoolyard before class. We were in the fourth grade. I remember their names--Sal, Andrew, and Stanley. I arranged our harmonies. We did “Please Please Me.” I noticed, on the “Come on, come on” part, that George stayed on the same note, while Paul’s “come ons” kept going up, so I had the guys practice that. We didn’t just sing in unison. We sang parts, even though we were only nine years old. The nuns would let us go around to the classrooms to perform. They gave us one copy of the “Meet The Beatles” album. We took turns taking it home on the weekends.

Where did you grow up? Was your environment musical?

I was born and raised in Manhattan (New York City) in the theater district so my mom took me to a lot of Broadway shows. At intermission I would always head toward the stage and look down into the orchestra pit. I was consumed by music. I saw “Oliver” with Davy Jones before he was in The Monkees. My mother was musical and my father was a professional musician, but I never knew him. My mother loved The Beatles and I liked Sinatra, so there was no generation gap there.

How did you begin to play music? How did your career start?

At the time of the British invasion, my mom bought me a Mel Bay book which had diagrams of chords. She didn’t play but she helped me figure the book out. I have an old reel to reel tape of me playing “Here There and Everywhere” using just three chords, which is quite a challenge, both for myself and the listener.

I guess my career started as a studio musician where I played guitar, bass, and sang on sessions, then getting into bands and playing gigs. First, original songs, where we got paid next to nothing, and then cover songs where we got more money.

How was playing with Tommy Makem?

I played with Tommy for about twenty years. It was a wonderful experience. He was a great guy. Very level headed, nice, and generous. He taught me a lot about performing with his stage patter and telling stories about the songs, which is easier to do with Irish folk songs than pop/rock songs. The subject matter is more varied. Because of him I got to play PBS specials, Carnegie Hall, and other beautiful venues. I saw first hand how respectfully people treated him and a lot of that came my way because I was his band. It was Tommy on banjo and myself on acoustic guitar and harmony. He would allow me to play whatever chords I wanted to his songs. His banjo was more pecussive than actual sustaining notes so we didn’t clash. It was fun musically because he had a good sense of rhythm and his vocal phrasing was consistant and made sense, so it was a pleasure to sing harmony with him. We talked about songwriting a lot. I got to witness when he first wrote a new song, like “Farewell My Friends.” He would want to end the show with a crowd pleaser like, “The Wild Rover” and I would say, “No. Do the new one.” He would say, “No—too dangerous.” Then when it came to the end, he would charge into the song I wanted. His encore, of course, was “Four Green Fields.”

AND he introduced me to George Harrison at The Bob Dylan Tribute after party. Dylan came to see Tommy perform at Makem’s so I met him too. Bono came to see Tommy play and I borrowed a guitar pick from him. That’s right—an actual Bono guitar pick!

What other projects were you involved with, apart from this and your solo albums?

In New York City, I worked at a recording studio (Dimensional Sound) and a film studio (Filmsounds). I did live sound at Folk City for local acts in Greenwich Village, but also Rick Danko, Peter Tork, Richard Thompson, Delores Keane, and Silly Wizard. I did live sound and lights at Tommy Makem’s Irish Pavailion on 57th and Lex., mostly for acts who were well known on the Irish scene. Once and a while you’d get someone like Bob Geldoff or Noel Harrison, who besides being an actor was a legit folk singer. After Noel played, one night, his Dad, came over to me and said, “More light! My son needs more light!” It sounded just like a Rex Harrison impression from “My Fair Lady.”

I did a U2 press conference at Makem’s. I played in a few Irish bands. Tommy was the biggest.

How do you write songs? What is your process?

It varies. Sometimes I’m fooling around on guitar or piano and a melody comes, and without thinking, some words pour out that sound like the right feel for the music. Then I have to make sense out of them. There are times when I start with a title, which suggests a certain type of music. Those lyrics are more focused because you know from the start what you’re writing about. Some songs are a sincere expression of what I’m feeling. You have to be careful with those because you can’t forget the craft that’s involved too. Otherwise it can be embarrassing or you’re the only one who gets it. Some are pure craftsman kind of songwriting, where you’re just working on writing a good song. Sometimes it’s an intersting chord change that is the inspiration. Most of the time they just come, rather then sitting down trying to write something. I wrote a musical and was given all the lyrics first. Someone else wrote them. The meter of the lines and subject matter, already having been written, made it very easy to write the music to it. I did it super fast. Not all the verses were the exact same meter so I had to adjust them to fit the music and visa versa. I was pleased with how it turned out. It was performed too. The musical was called, McGoldrick’s Thread. Marianne Driscoll wrote the book and lyrics. I’m thinking of releasing my original demos of the songs along with the overture. I have to clear it with Marianne.

What were the recording processes for your albums? Good memories or hard times?

They were good memories because I was so driven to write and record. It was also hard because I never had the recording equipment that I needed to do what I heard in my head. Analog, unless you can afford great stuff, is a lot of work. You have to bounce harmonies from maybe six tracks to one track, especially when you’re doing all the parts yourself. You lose generations and hiss builds up. I think I got the best out of it though. I did get inspired every time I got a new tape deck with more tracks. I went from two track “sound on sound” recording, to four track and then eight track. If I wanted more, I would have to go to a recording studio--constantly watching the clock and hoping the engineer would keep track of any “down time.” That’s time the studio would deduct from your bill if it was their fault things were taking so long. Digital is so easy and inexpensive—endless tracks. I love it, but my boys love analog. They’re very “retro.” Engineering yourself can be clumsy too. You’re trying to play your instrument and you have to adjust some equipment. You’re getting up and sitting back down. You’re putting nicks in your guitar trying to hold on to it, while you’re trying to punch in and get back to your instrument in time. It’s tiring.

Probably your best known story, until now, is that of Falling for Love,

your song recorded by The Carpenters. Can you tell us about it?

In 1981, I mailed “Falling For Love” to three different places—the label A&M in LA, their agent, and their manager. Richard Carpenter heard it and liked it. He liked my version too. The Carpenters recorded it with Karen doing a rough vocal. She was very sick and in a New York hospital. She died before doing a final take. Richard said her guide vocal wasn’t good enough to release. I never heard their recording.

How was the contact with You Are The Cosmos made?

Pedro Vizcaino, who owns the label, messaged me through Facebook. He asked if he could release it. He heard about my music from his friend Pablo, who might have listened after he heard The Lemon Twigs talking about Dad’s music. Pedro really has a love for powerpop and was so excited about my stuff that it was contagious and I said yes and thank you.

How has the process of releasing the box-set and LP been?

Pedro and myself did it all through email. He’s in Spain and I’m in the US. We went through all the artwork and album information online. Besides releasing the 3CD Box, he wanted to put out a “Best Of ” from the three albums. We made the list together. The Box and Vinyl was his idea. His artist came up with the album cover for the vinyl. I gave them some pictures from that period.

What can we expect of those releases?

It’s a nice package to have, and I think people, who like pop/rock, will like it. I hope it sells and we can press more. I’m looking forward to the next one. YouAreTheCosmos is releasing my latest three Cds in the same way over the summer. That includes a brand new album that I just finished called, “The Many Moods Of Papa Twig.” The other two are, “A Very Short Dream,” and “Time Will Tell On You.”

What do you think of music in the Internet era? Is digital really the future?

Well, having been through analog, I think digital is a marvalous and easier way of recording. That goes for video too. I do respect the people who prefer to stay in analog. The thing that bothers me about digital is mp3s. We finally got to the point where you can now hear at home the same quality that we heard in the recording studio, and then comes mp3s, that are compressed for convenience so you can fit five hours onto a cd and even more on a DVD, but the fidelity isn’t as good. Plus people listen with ear buds that don’t reproduce the bass unless you press them against your ears. Now folks are getting used to listening to music out of the tiny speakers on their laptops. One of the great things about the Internet is that everyone has an outlet for what they want people to know about. This collection was a result of that. I hope the future has some room for melodies and films with good stories. It’s good to see young people at concerts like The Zombies Odessey and Oracle tour. The whole row behind us was teenagers. The Beatles have touched every generation for five decades. So has Sinatra, who was even before my time. The fact that The Lemon Twigs are making inroads with their songs is a good sign. I work in a high school and most of the students seems to prefer classic rock. Michael and Brian do new music, but they’re well written songs, so all ages seem to like it.

Your sons are conquering the world. How was raising them?

How did they learn music?

They were in show biz since they were nine—Broadway shows, TV, movies, and now music, which was always their first love, more than acting. They learned music from having instruments and recording equipment all around them. I taught them simple drum beats, guitar chords and licks. I demonstrated different types of chords on the piano and trained their ears so they would recognize, say a diminished chord, or a major seventh. They were born will musical ability and my wife, Susan, and I would point them in the right direction. They took it from there and learned the rest on their own very quickly. Susan was responsible for their acting. She used to be an actress. I think that added to there ease on stage. She also sings and has an ear for harmony. They were, and are, such cute kids—very smart and funny.

You should be proud of the Lemon Twigs!

How was working on their debut álbum as a father? How much input did you have?

The only thing I did technically was mix “How Lucky Am I?” But they always play new things for me and I give them my opinion and suggest things and they do the same for me. I taught them how to use my recording equipment and they experimented on their own too. Rado, from Foxygen engineerd and produced them in LA, and Brian mixed their album in our basement studio. I would come down once and a while and suggest things. Brian picked it up very quickly. I went with them to master the album, but just as another ear. They were definitely in charge.

Do you remember one or two especially great moments in your career?

And maybe an awful one?

Having my song recorded by The Carpenters.

Having my my song unreleased by The Carpenters.

How is Mexico viewed from there?

They shouldn’t pay for that fucking wall! Selma Hayek is a babe. I love mole’ sauce.

Now, a question I kind of love and kind of hate (you can pass!)

Can you name 10 essential records for you?

I’ll keep it down to two albums per group. I need 20 and this is not in order.

Do Hollywood - The LemonTwigs

Revolver – The Beatles

Magical Mystery Tour – US version – The Beatles

Pet Sounds – The Beach Boys

Greatest Hits double album – The Beach Boys

Procol Harum (with AWSOP) – Procol Harum

A Salty Dog – Procol Harum

Ram – Paul McCartney

September of My Years – Frank Sinatra

Emitt Rhodes – Emitt Rhodes

Brazill ‘66/Antonio Carlos Jobim – Best Of

Badfinger - No Dice

Himself - Gilbert O’Sullivan

Carousel – Richard Rodgers & Rhapsody In Blue – George Gershwin

HMS Pinifore – Gilbert and Sullivan

Casino Royale 1967 soundtrack by Burt Bacharach

Dionne Warwick/Burt Bacharach (on Rhino Records)

Motown Hits – Various Artists

The Four Seasons & Leslie Gore & J.S. Bach – Greatest Hits

The Kinks – Kronickles

Lovin’ Spoonful/Mamas and Papas/Byrds/Dave Clark Five – The Hits

I like The Stones too.

Randy Newman – Sail Away & Good ‘Ol Boys and much more.

Okay--I cheated a little.

As a closing line, anything else you’d like to add or recommend?

Just to thank you and every one out there for their interest and kind words.

Thank you.

RONNIE D’ADDARIO interview 4/12/1

Your first album, Take In a Show, was released forty years ago.

What did you do, as a musician, before recording your own songs?

It was never released until now. People are more open minded about home recordings. This album was done on a Teac 4 track deck with one mic on the drums. If anybody showed interest back then, I probably would have re recorded it. I hate re recording songs because you're just repeating what you did but with better equipment. I was writing songs since I was eleven, but I don’t think I had anything decent until about sixteen.

While recording that album, I worked in a recording studio, a film studio, and at Sam Goody’s for two weeks. My job was filling the plastic record covers to replace a record that had just been sold. I was fired because I kept falling asleep over the record bins. I didn't pass the two week trial period. One great thing that came out of it was, I was given tickets to see The Raspberries and Stories at Carnegie Hall. The guy who now runs Beatlefest was the manager at Goody’s and he took pity on me. Amazing show!

My kids really love my first album, including the way it's recorded, which made me appreciate it again.

Also Darian Sahanaja (Brian Wilson & The Zombies) digs it, which means a lot to me.

What or who gave you this opportunity to make an album?

Myself. I bought recording gear, I had a Gibson SG guitar, a $25 Greco bass, which was a Hofner knock off, no piano so I sped up my guitar. For guitar distortion, I blasted out my VU meters on the tape deck. I took my 4 track to my friend, Paul Rutner's house, and played his drums to a click. I also had a $40 Kay F hole for my acoustic guitar. It's all in there.

You made that first record at home, at a time when it was unusual to do that. You were pretty much a one-man band?

Paul McCartney and Emitt Rhodes did it in 1970. Todd Rundgren and Stevie Wonder did it later on. But I even did it when I was a little kid playing around with my mom's Revere tape recorder and in High School using "Sound on Sound." I guess I didn't have a band until later on, but even then I recorded mostly on my own.

Your style of writing and singing was very close to Macca, Brian Wilson, Colin Blunstone...

Did you learn to write songs by listening to their records?

Mainly Beatle records and later on, into the seventies, I got into the Beach Boys. I also took a crack at standards because I loved Sinatra. Bossa Nova was great for discovering interesting chord changes. I loved Gary Brooker and Procol Harum. Still do.

What record really changed your life?

Meet The Beatles, of course! Later on, "A Salty Dog" & "Surf's Up." Those were the first Procol and the first Beach Boy albums I got into.

Where did you grow up and how did you discover the artists that inspired your own music?

Midtown Manhattan (NYC) in the theater district, across from the Ed Sullivan Theater. I was walking home one time and I heard this commotion in front of the theater. I went over and I saw girls screaming and by accident, of course, they pushed Mick Jagger through the glass doors. Then they were crying and asking, “Is Mick hurt?”

I also went to boarding schools outside of New York because my mom was a single mom. She worked a lot of overtime to support us.

As far as discovering music, like everyone, I discovered The Beatles watching Ed Sullivan. I heard British Invasion stuff and everything else on TV and mostly radio.

I remember hearing and liking “The Four Seasons” before The Beatles hit.

I heard show music a lot too because my mom would take me to a lot of Broadway musicals. We lived right there. I saw Davy Jones play the Artful Dodger in Oliver. That was pre Monkees. My favorite show music is “Carousel” by Richard Rodgers. I never saw that show live, though, because it was way ahead of my time

What was so fascinating about them?

The Beatles? Everything! Their music, the way they looked, their attitude, humor, etc. You know that feeling you get when you first hear music that moves you. It gets to your brain and body. It’s indescribable. It doesn’t happen as much nowadays. Maybe it’s a combination of getting older and being more musically sophisticated, along with the fact that there’s not as much great music happening.

Did you meet some of your heroes?

I met George Harrison at The Bob Dylan 30th Anniversary Tribute after party. Tommy Makem, who I played with, introduced me to him. He said, “Hi Ronnie.” I met Dylan, although he wasn’t a hero, but I do like him. I was at CBS records in the seventies. I got on to the elevator and Beach Boys Mike, Al, and Dennis were in there with me. Al was very shy, Dennis was incredibly friendly, and Mike was polite. I met Carl at The Bottom Line during his solo tour, and I met Brian, at The Broadway show—“Good Vibrations.”

I met Burt Bacharach at a Dionne Warwick concert. I interviewed Gary Brooker from Procol Harum, which is posted on their web site. I met Matthew Fisher as well.

In 1976, the great era of pop music that inspired you was about to end.

Would you say that you were not made for these times?

Maybe, but in the circle I hung out in, we always liked this kind of music so I didn’t feel out of step. The Lemon Twigs don’t feel that way either. They just continue to do the music they like. They’re not trying for any kind of sound. It’s just what comes out of them. I never tried to sound Beatles or Beach Boys; in fact, many times I try not to sound that way. I think when someone writes melodic songs, people think--The Beatles. If someone hears harmony, it’s The Beach Boys. I am influenced by them, but I’m influenced by everything else too. Badfinger is like heavy Beatles at first, but then you start to hear them as Badfinger.

You’ve never been bitter or frustrated because of the lack of success of your own records?

Of course I have, but I was never good at pushing really hard, like a Madonna, who wanted it just as much, but was willing to work really hard for it. I shopped around a bit. Unfortunately, I never ran into anyone heavy enough who could help me. I didn’t know how to network, and after writing music, lyrics, playing, singing, engineering, producing, and arranging, I guess I didn’t have what it takes to be a manager too.

I never thought I wasn’t good enough.

I wish I had had digital recording and social media back then.

Have you always been very serious about your music or was it just a hobby with no ambition, except taking pleasure and have fun?

I’ve always been serious about my music and my ambition was to be very successful, and make that my only living. I’m amazed that I have a pretty substantial body of work, considering I had to do it while holding down a job and supporting a family. My friends that started with me are not very productive musically anymore, except for playing live gigs for money, but no original music anymore. I understand that, but there’s something in me that makes me keep doing it. It’s weird. Sometimes when I’m recording, instead of thinking, “forget this, no one is going to even hear it, so what’s the point?” I start thinking about certain friends who have been fans for years. I’ll think this person will really dig this--Brian, Michael, Buddy, Nick, Chris, Fran, Beddy, Johnny, Stewart, Greg, Glen, Darian—You really have to psych yourself up to keep going.

What was your daytime job when you were not playing music?

I was always playing even when I was working. My jobs always involved music or audio engineering. I worked for years as a soundman at Tommy Makem’s Irish Pavilion, which was a night job, BTW. I would get subs to fill in for me when I had a gig. Even now, I work in a High School. There’s a recording studio there, where I work. That requires my services as an engineer and musician. I have a club of students who I teach live sound to, and stage lighting. We do the concerts and plays, and whatever else the school needs.

You wrote a song for the Capenters in 1981 but it has never been released, do you have regrets about that?

I had a lot more songs that would have been good for them.

I wish that it was released and that Karen had lived.

How close were you with Richard and Karen?

I didn’t know them at all.

Would that song have changed everything if it were released?

Probably.

When your sons started to play instruments at home,

what was your role in their musical practice?

I taught them simple drumbeats and coordination, simple versions of guitar and piano chords, helped them learn the recording equipment, and sang harmony with them. Brian was older so I worked with him first. Michael was just interested in drums. When he got older, he became interested in guitar, piano, and bass. At that point Brian and I both helped him. They went way beyond what I taught them. They were driven--Never put their instruments down.

Were you jamming all together on Saturday and Sunday afternoon?

Yes, we would play together in the basement where I had a PA system and lots of different instruments. We would switch off. They learned how to sing through a microphone.

They first appeared on your album A Very Short Dream.

How was it to have them singing one of your songs?

It was nice. Instead of baseball, we did music. They were very young on “Trophy Girl.” They were a bit older on “My Old Self Again” and on the new album, they sound like they do now on a song called, “She Tries.”

Have you yourself been raised in a musical family?

Yes. My mother had a good voice and a great ear for harmony, as does my wife, Susan. My father, who I didn’t know, was a professional musician--a sax player. He played with Sinatra, Dionne Warwick, a lot of people. He played the horn break on “Let’s Hang On” by The Four Seasons.” He also played golf a lot with Frankie Valli. I wish he would have stuck around.

Had you noticed very early that Michael and Brian were truly gifted?

Yes. They were good actors too. They acted professionally. They were on Broadway, TV, and films. Brian was in Les Miz, and The Little Mermaid. Michael was in All My Sons, John Adams on HBO, People Like Us, and Sinister. Brian did CSI and Law and Order. Michael was in the TV sitcom, Are We There Yet. They both sang great even before they started playing instruments.

What kind of advice did you give to them when they were about to make an album?

I told them to record digital. It’s easier, cheaper, and sounds great. They went analog. They’re retro. They would play me songs, and I might say something like “It’s not structured enough. I don’t know where the verse ends and where the chorus begins, but I like the music.” They recorded all the songs as demos before they went to record with Rado in LA. They only had two weeks to finish, so they made sure that the arrangements worked. I helped with the mixing. They weren’t sure about the original mixes. I did some mixes on my own just to show them the difference. That confirmed what they were thinking. They didn’t like the original mixes either. So Brian mixed the album and I would come down to the studio and offer some audio advice. He asked me to mix “How Lucky Am I?” which he was having difficulty with.

Now they are playing some of your songs on stage, do you take it as a sweet revenge?

I don’t know about “revenge.” I’m just glad that they like my stuff enough to perform it. They do a great job on it too. When they played New York, I got up on stage and played it with them, which was nice.

You’re about to release a new album called The Many Moods of Papa Twig, in reference to the Murry Wilson album I guess?

Exactly. That came out of my boys posting my music on Twitter saying, “Check out the genius of Papa Twig.” So they came up with the name “Papa Twig” and I liked it. So because their success sparked an interest in me, I thought there was a parallel there, even though in Murray’s case, Capital Records released his music mainly to appease him. When articles are written about them, the magazines always like an angle. The most popular one seems to be that their dad is a musician too and turned them on to great music. Then when people check out my stuff, they see similarities. People find it interesting and it gets a buzz going, which is a positive thing.

How about the reissues of some of your stuff in a box set and compilation?

Was that made possible because of the success of The Lemon Twigs?

Sure. They mention their dad a lot in interviews. They peak people’s interest enough so that they’ll go online like YouTube and check me out. Then those people spread the word and on and on—that’s how social media works. This fella, Pablo Milea, heard it and recommended my music to Pedro Vizcaino, who loved it, and wanted to put it out on his label, “You Are The Cosmos” Records. Pedro loves power pop and is so into what he does that he gets you excited too. He’s been great. These recordings are not reissues. This is the first time they’ve ever been released.

http://islandzoneupdate.blogspot.com/2018/09/papa-twig-revealed-conversation-with.html

Island Zone Update

Exclusive interviews with extraordinary musical artists by veteran music journalist Roy Abrams

Saturday, September 29, 2018

Papa Twig Revealed:

A Conversation with Ronnie D'Addario

Great new music is discovered in a myriad of ways, as experience has taught me throughout my life. Perhaps the most unusual introduction took form in the shape of two sons’ praise for their father. Given that the sons in this case were none other than Brian and Michael D’Addario, better known as the Lemon Twigs, my curiosity was instantly piqued. Ronnie D’Addario has been quietly recording and releasing music for the past four decades, and may well have escaped my radar altogether if not for his sons’ recognition of their father as a primary influence upon their prodigious songwriting talent. With the discovery process now underway, I soon realized two things: First, that I needed to thank Brian and Michael for the recommendation; second, that their father is a songwriting wizard whose sense of melody, harmony, and arrangement calls to mind both Paul McCartney and Brian Wilson. That’s no hyperbole; that’s fact.

The first track I listened to, “The Walking Wounded,” sounded as if Macca himself had magically teleported into the session to contribute vocals to the song’s outro. The song embedded itself into my consciousness, and for days on end, no matter where I was or what I was doing, there it was. Then, embarking on a quest to digest Ronnie D’Addario’s vast musical output, I soon realized that a major songwriting talent has been quietly lurking in our midst. In reaching out to arrange an interview, I asked Ronnie if his sons wouldn’t mind contributing a list of their individual Top Ten favorite “Dad” songs as a guide to discovery. Happily, they agreed, and while listening to the tracks they listed, it was readily apparent that Dad has played a major role in shaping the unique songwriting talents of each of his sons.

And so it was that on a beautiful July afternoon, I found myself sitting across from Ronnie D’Addario in the living room of his Long Island home, where we ended up chatting for more than two hours about—well, about a whole lot of things. In the process, I got to meet and make friends with the two family dogs (shout out to Mona and Bruce!), chat a bit with Brian and Michael, and soak in the aura of an extraordinarily close musical family.

Here is our conversation, slightly edited for clarity. Read and enjoy!

Roy Abrams: This is an interesting situation. I discovered your music through your sons. To have that introduction come from such an unlikely source is a unique occurrence. I thank your sons! Now, we’re both die-hard Beatles fans--

Ronnie D’Addario: Yeah.

RA: --and I’m sitting and listening to your music and … well, on the outro of “The Walking Wounded” I said to my wife, “It sounds like Paul McCartney is doing a cameo here.” Your ear for harmonies and the arrangements bring to mind not onlyThe Beatles, but also Brian Wilson, The Zombies, Burt Bacharach, and Gilbert O’Sullivan. The earlier albums have a Paul/Wings from the early ‘70s vibe and your later albums have more of the feel of Paul’s recent “Golden Age”, from Flaming Pie toMemory Almost Full.

RD: I think I got more into layered harmonies later on, and that was mainly because I had more tracks. Also, because I got into The Beach Boys late; I got into them with the Surf’s Up album in ’71. I never paid attention to them when I was a kid, which is weird. I was so involved with the British Invasion and everything, and, you know, like everybody, after Sgt. Pepper, you’re into The Doors and Cream, and all that stuff. I love the later Beatles stuff, but in terms of bands like the Doors and Cream,Led Zeppelin and all those bands, my heart is more into the earlier pop music where it was more song-oriented. I mean, I liked that (other) stuff because you’re at the age where when your friends like it, then you like It … Hendrix and all that … but I was always geared more towards songs.

RA: You saw the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show at age 10 and started playing the guitar as a result. Having listened to your music virtually incessantly for the past several days, I can hear that the Beatle roots run deep.

RD: Yeah.

RA: Can you place yourself back in front of the TV while that was going on? What were you feeling?

RD: Yeah. Amazement, like everybody else who was my age—or younger or older—the music just went through me … you know how when you were a kid, that music goes through you and you get that feeling and you seldom get that again when you’re older. I mean, once in a while you do, maybe because you’re more educated musically, or things aren’t as good, but when I saw them, the way they looked, the way they played that type of music … it knocked me out. I did nothing but think about it!

RA: And you started playing guitar right around then?

RD: Yeah, my Mom bought me a guitar that summer. I figured everything out with three chords, got everything wrong, learned some licks.

RA: When did your first band come along?

RD: My first band wasn’t for a while. I wasn’t in bands when I was a kid. In fact, I was usually the only guitar player in my school, because it wasn’t as prevalent then. I remember in fifth grade, we did a performance of Charlie Brown [sings: He’s a clown!]I was playing guitar, and my part was “why is everybody always pickin’ on me?” …and the nuns laughed. I went to both Catholic and private schools, which is the worst thing to do, because you get used to freedom and then you’re in a regimented thing … but that’s a whole other story! Just out of high school, I was in a band with my two cousins, Randy and Johnny, and we just did a lot of Beatles songs. Not much has changed. Then, I worked in a studio in Manhattan a block away from my house. I was on 54th between 7th and Broadway, and place was on the corner of 54th and 8th, called Dimensional Sound, and that’s where I met a lot of the friends that I still have. We worked for no money--$15 a week lunch money—and made friends with a guy named Paul Rutner, and then he introduced me to Nick Lohri and Buddy Zech, and all these Long Island people, so I would get picked up at the Wantagh train station; every weekend, I would stay at his house for two days, and we’d rehearse all weekend. We did The Who, The Beatles, The Hollies, all those bands. We also did Bowie and that kind of stuff. We never played out much. We were just a “basement band.”

RA: As most bands are at that time!

RD: Yeah! I remember we might have done two gigs at a place called The Iron Horse. Do you remember that place?

RA: The name rings a bell. Was it in Babylon?

RD: It was probably in the area. At that time there was My Father’s Place which—I think they’re open again?

RA: Yeah, it’s in the Roslyn Hotel. Eppy’s back and involved with it.

RD: Well, we weren’t big enough to play there. In that band, I remember we started rehearsing “Take In a Show.” That was the first time we started doing an original, but then we all got so frustrated that we just broke up. We didn’t know anything. I remember when we lost our guitarist we did the typical thing (of) putting in the ads in the Village Voice. You know how they always have “We’ve got Pete Townsend and Roger Daltrey, we need John and Keith.” So, we all had these lists that said instrument, tastes, how he looked, and then age: “26—too old!” [chuckles]

RA: I remember those ads …

RD: So, that was the first band I was in. I think we were called The Quick, then I was in another band with a lot of the same guys called The Noise, and then maybe two changes of members and there was The Firemen, then there was The Press …. (the bands) always had some of the same people in it. That’s where the kids (got it), before they were doing the Lemon Twigs, they were Members of The Press. They got that from our band. Now, I’m still in a classic rock band. I was in an original band; we tried it, but nothing happened. I’ve been in this band for 30 years and we used to play every weekend, doing the same songs. We didn’t want to get heavy; we didn’t want to be this major cover band that had this great equipment (and) had to rehearse and learn every latest song. We just did the same songs we’ve been doing since fifth grade … mostly ‘60s and ‘70s, some ‘50s stuff like the Everly Brothers andChuck Berry; not the doo-wop stuff. So, Paul Rutner was the drummer, and I went to his house, and he had a drum set, and that’s where I did all the drums for Take In a Show. We had one crappy microphone that actually sounds okay, but I had a click track and a rhythm guitar, and I knew the songs inside and out. I hardly ever played drums—it was always on my knees, because I didn’t have a drum set! So, I ran through it once, and he recorded me with one mic onto one track. I think I did all those drum tracks in one day, and then took my 4-track home and overdubbed the rest. That was in 1976.

RA: When did The Muse first hit you, as a songwriter?

RD: When I was eleven. I’ve got the whole list. I used to write (them) down; I don’t do it much anymore, but I have a list of every song that I’ve ever written, what year it was, how old I was. My first songs were just kind of ridiculous. I don’t know how this is gonna sound in an interview if I sing it, but [sings} I love you and I wanna be true … I love you, please don’t make me blu-u-u-u-ue. Now, that’s right out of Beatles (song), probably “Ask Me Why” or something. [chuckles] Then I had this ridiculous song called “I Nearly Died.” The lyric was “I nearly died”, from “No Reply” and the music was from “There’s a Place.” I used to have recordings of all those. When I was in high school, I was listening to it one day, and I got so embarrassed that I erased it, which was the dumbest thing, because now I wish I had it. My Mom almost went nuts when I told her. I had a little Revere tape recorder when I was a kid, so I always had stuff like that around. I had that when I was nine, playing with this little tape recorder.

RA: When did you first start to pursue a record deal?

RD: Probably after I did that Take In a Show album, so ’76. I was 21. What I did was, those (tracks) to me were demos, really, and I remember going into Media Sound, a recording studio, and trying to get a spec deal. Now, I wanted to record them over, and they liked it, but they just didn’t … maybe (because) it wasn’t disco or something; I guess I wasn’t doing stuff that was “happening” … there was a lot of disco around at that time. In fact, I was in a studio band at Dimensional Sound where we would cover all the records of the time; it was “not the original artists,” it was us. I’d hear myself singing “Laughter In the Rain” on TV. [mimics announcer’s voice]“Not the original artists!” And you’d get maybe 20 hits for five bucks, or whatever it was, and the grooves (on the record) were really small. And they were horrible. We would take eight songs home on a Friday, come in on Monday, and knock eight things off. They would have the original record on track 24. We played along, listening, and we sounded dead because we were listening to it. Once in a while the drummer would take an extra roll because it was a tricky 9-bar verse instead of 8. It was good for my bass chops, because there were a lot of cool bass lines going on.

RA: There are a lot of cool bass lines in your music.

RD: Oh, yeah. Especially earlier; I don’t do that much now.

RA: That’s interesting, because it’s the same trajectory that McCartney took. He still does some really cool bass lines here and there.

RD: I don’t know why that happens. Maybe when you’re younger, you’re really driven, you want everything to happen, and then when you’re older, you want the song to be the thing.

RA: I know what you mean; the focus is elsewhere.

RD: Yeah! But I still love when I hear McCartney doing great bass lines on his records, and I do enjoy nice bass lines. I got a little bit more into that on that last album (The Many Moods of Papa Twig) because the kids were pushing me on that.

RA: The production displays a great deal of thoughtfulness.

RD: You know, that first album, I kind of just forgot about it; they’re the ones that really liked it. They said, “We love that one because it’s all real instruments.” Later on, I got into a little bit of MIDI stuff, which I tried to make sound real. I think they’re good piano sounds, decent string sounds, but if you listen to their new album, their strings sound great. They had string players; in fact, some teachers from their high school.

RA: One of the things I hear, as a songwriter, is your attention to arrangements. There’s nothing cluttered about them; there’s a lot of air.

RD: I try …

RA: When you’re writing a song, are arrangement ideas starting to gel in your head while it’s happening?

RD: Yeah. I’m definitely hearing arrangements while I’m writing, which is why sometimes in a band situation—because I’ve been in some bands where we were doing originals—a band called The Rock Club, and again, you can probably compare it to McCartney, but because these arrangements come to you when you’re writing a song, when it comes time to rehearse (it) with a band, you want to give them some parts … which is, in one sense, unfair to them because (for example) the bass player would say, “Well I really wish you’d give me a chance to come up with my own parts.” And I would say, “This is part of the song.” It’s like if you wrote “Day Tripper” and you had this lick, and you said, “This is the lick,” (and the response was) “Let me come up with my own, since I’m the bass player.” “But that’s the lick!” And so, I had a tendency to do that, but having known what happened with The Beatles … we use them as all our yardsticks, for every pitfall every band goes through, they’re the ones that went through it first (at least to us, they were). I knew the resentment that could happen, so I would always try to be diplomatic, whereas I don’t think McCartney was diplomatic. Maybe he tried, but you could hear the resentment from the other people, except Ringo, who I’m sure welcomed his drum parts. But you’re right—these arrangements come out of nowhere, thank God! I don’t usually have to work that hard on a production because when I’m writing a song, because by the time I finish the song, I’ve already got all these parts! I didn’t have to work. I mean, you have to do some work! I just hear it; I’m not forced to work really hard to do it.

RA: Does the same thing apply to your harmony stacks?

RD: Yeah! Well, if it’s a song that really depends on harmony, then … when I was younger, I would just work hours and hours and hours. I couldn’t believe Brian yesterday—he wrote a new song, and he worked on it for frickin’ twelve hours. I remember I used to do that—I can’t do that now! I go three hours, I’m shot. Just trying to get the energy to even start is not easy. Back to your question, sometimes my goal is to do as little as possible. I want to fill up wherever the song needs without exactly having to add too much. And so I put in everything that the song needs, as little as possible, so I don’t have to do the work. This sounds weird! But then I’ll listen and go, “You know what? It sounds good; I could leave it.” But I, as a listener, am missing those oohs, those aaahs, little answering things. I got all the basic things; the one harmony line topping the lead here and there, and I’m trying to get away with not doing all these pads, these chords … maybe I can get it with just holding some strings down. But you know what? When I listen to The Beach Boys, I like to hear those harmonies, and I think when people listen to my stuff, they’d probably like to hear that, so I go, “Ah, hell!” [chuckles] and I’ll spend another thirty hours. You know?

RA: Yeah!

RD: It’s almost like playing games with yourself to try and get through it. Now, sometimes I’ll be incredibly inspired, and I’ll work longer. But it’s hard to … I don’t know how you feel when you’re writing, whether you’re totally enthused … it’s hard to get up that energy to start. I’d just as soon get out of bed, watch TV, eat, take a nap, get out of bed again, have another meal, watch TV … but I know those days when I get up and I hop in the shower and (think) ”Okay, I gotta do something now because I’m not greasy, I don’t gotta hide away!” I’ll tell you something that inspired the last two albums. I had a lot of songs from the ‘80s that always hung over my head, because I couldn’t get up the energy to record them. I record all day at work, by the way. We do an album a year, and every other year we do two albums; one’s a Christmas album, one’s a regular album. So, I must have done 200 songs for that school.

RA: When you say “regular album” you mean ….?

RD: They’re Christian albums, but it’s pop/rock stuff but with Christian themes. I’ve even written some things for them. So, I’m recording every day … so to come home try and work on my stuff … I’m kinda shot. But you know, I said, I wanna get rid of (these songs). I wanna get ‘em on—I was gonna say on tape!—I wanna get them recorded before I croak, and before I lose my voice … because I’m seeing all these people that are having a hell of a time singing now. Some of them can still do it; some of them can’t. The other day, somebody posted a performance that John Sebastian was doing. He does that storyteller type of thing, and he’s completely shot. He lowered the key (which McCartney doesn’t do) but he still couldn’t … [whispers} “Do you believe in magic?” So I was thinking, boy, I better get all these songs recorded. The last two albums--A Very Short Dream and The Many Moods of Papa Twig—about half of the songs on each album were already written years ago. The newest song on Papa Twig was “Love Unconditional” which I wrote for my boys, but “The Beginning of the Day” or “Get It Right” were written in the ‘80s. In one way, I’m kind of glad, because if I would have done them back then I wouldn’t have as good equipment, but for years, that always bothered me. What also helped was the kids getting with 4AD, and You Are The Cosmos Records getting in touch with me, wanting to release my stuff, that kind of gave me a little bit of incentive, too.

RA: The first time I heard “Get It Right,” I was driving, and I pulled over so I could completely focus on the music … and here’s a strange question for you: Have you ever attempted to make any inroads into the Macca camp?

RD: I wish! I mean, I’ve never met Paul, and I’ve never attempted to try and get something to him, because I don’t know how to do that, and now that the kids have some connections (because everybody’s connected a little bit), I don’t want to impose on them. It’s funny … you say (to yourself), the minute I get an “in”, I’ll do it.” Well, now I have an “in” but they’re my kids, and I don’t want to bug ‘em when they’re trying to do their career. I’ll tell you a funny story, talking about the McCartney thing: Brian was sitting on the couch, texting for a long time. (Finally), I asked him, “What are you doing?” “Ah, I’m texting Mary McCartney.” “Mary McCartney. Paul’s daughter?” I ask. He goes, “Yeah, she likes us.” And they’re there for a half hour, texting. She wants to meet them, or if they’re in England. She took a picture of them coming out of Abbey Road Studios, and they didn’t even know it! She recognized them and took a picture, which is on my website. So then, you think, wow! That’s one step from meeting the big guy! But then you think, what am I gonna do? Ask the kids, “Hey, can you get my stuff to ... ?” Sometimes I think of a song that might be good for an artist, which I think is more realistic than try to say to somebody, “Hey, Paul! Could you get me a record deal? I’m 63! All the kids love that!” You know, I got a gimmick! We’ll work backwards!” [laughs] But, I’ll have a song like “A Drunk Man Speaks a Sober Man’s Mind” … a lot of people tell me I should get that to Vince Gill. (I had written it mainly for George Jones, but he’s not around.) So, I’m thinking, that’s a pretty good suggestion. I looked up one address, an agent or something, but then I thought, “Hmmm. I wonder if I should ask the kids’ manager if he’s made any “ins” but it’s almost like … I don’t wanna … you know, they’re busy with their own careers.

When I was younger, I thought, instead of these record company slimes, if only I could get to an artist, but then I thought, even if you do that, they’re busy with their own careers. It’s very rare that you get somebody like Foxygen, who the kids liked, and sent Rado their tape, and he actually said, “I like this!” Brian said (to him), “Will you be our Richard Swift?” Because that’s what Foxygen did. They gave their (tape) to him, and he liked them, and he helped them. And Jonathan Rado helpedthem out. That’s part of the whole media … they did it through Twitter or something. And that was great. Now, if that hadn’t happened, who knows what would have happened with the kids? Although, they’ve been successful their whole career; even on Broadway, they’ve had a lot of good fortune—as well as talent, they’ve had some good fortune, too. Back to the question, sure, I’d love to! I was on Al Jardine’s bus because I got to be friends with Darian Sahanaja. What happened with that was, one day on Facebook, I said, “I got a song on New Girl, “Take In a Show”, they’re going to place it on the show.” All of a sudden, out of nowhere, Darian says, “’Take In a Show’! I love that song!” I went, “WHOA!” That’s the guy who putSmile together, and he’s the musical director for The Beach Boys, he’s played with The Zombies … and we became friends. He got us tickets to a Brian Wilson show and got us backstage; the same with The Zombies … and I was on Al Jardine’s bus, but I’ve got the kids there. Now, in the old days, I would have had a CD with me, always! But what am I going to do? I’ve got Al Jardine, Darian, my two kids … “Hey, Al! Here’s my CD. I think you’ll really dig it.” I don’t have the nerve to do it now. And, what would happen if I did do it, I ask you? I mean, it would be great if he liked it; that would be nice.

RA: The presence of your influence upon your sons’ music is palpable.

RD: Yeah, they’ve been telling me that. Michael said (that) when he was writing that song, “Lonely,” he was saying, “Dad, I’m trying to write a song like you!”

RA: Their biggest musical influence happens to be one of their parents. That’s a mind-blower to me.